Preventative Maintenance Plan Template

Tags: maintenance and reliability, planning and scheduling

Tags: maintenance and reliability, planning and scheduling

Introduction

Creating a maintenance plan is generally not difficult to do. But creating a comprehensive maintenance program that is effective poses some interesting challenges. It would be difficult to appreciate the subtleties of what makes a maintenance plan effective without understanding how the plan forms part of the total maintenance environment.

This article explains what makes the difference between an ordinary maintenance plan and a good, effective maintenance program.

Defining the terms

Maintenance practitioners across industry use many maintenance terms to mean different things. So to level the playing field, it is necessary to explain the way in which a few of these terms have been utilized throughout this document to ensure common understanding by all who read it. It must be emphasized, however, that this is the author’s preferred interpretation of these terms, and should not necessarily be taken as gospel truth.

In sporting parlance, the maintenance policy defines the “rules of the game”, whereas the maintenance strategy defines the “game plan” for that game or season.

- Maintenance policy – Highest-level document, typically applies to the entire site.

- Maintenance strategy – Next level down, typically reviewed and updated every 1 to 2 years.

- Maintenance program – Applies to an equipment system or work center, describes the total package of all maintenance requirements to care for that system.

- Maintenance checklist – List of maintenance tasks (preventive or predictive) typically derived through some form of analysis, generated automatically as work orders at a predetermined frequency.

- Short-term maintenance plan (sometimes called a “schedule of work”) – Selection of checklists and other ad-hoc work orders grouped together to be issued to a workshop team for completion during a defined maintenance period, typically spanning one week or one shift.

The Maintenance Information Loop

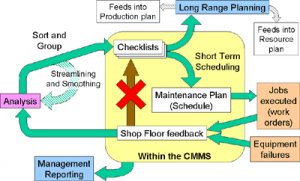

Figure 1 below describes the flow of maintenance information and how the various aspects fit together.

Figure 1 below describes the flow of maintenance information and how the various aspects fit together.

Figure 1 – Maintenance Information Loop

The large square block indicates the steps that take place within the computerized maintenance management system, or CMMS.

It is good practice to conduct some form of analysis to identify the appropriate maintenance tasks to care for your equipment. RCM2 is probably the most celebrated methodology, but there are many variations.

The analysis will result in a list of tasks that need to be sorted and grouped into sensible chunks, which each form the content of a checklist. Sometimes it may be necessary to do some smoothing and streamlining of these groups of tasks in an iterative manner.

The most obvious next step is to schedule the work orders generated by the system into a plan of work for the workshop teams.

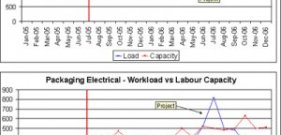

Less common, however, is to use this checklist data to create a long-range plan of forecasted maintenance work. This plan serves two purposes:

The results can be used to determine future labour requirements, and

They feed into the production plan.

The schedule of planned jobs is issued to the workshop and the work is completed. Feedback from these work orders, together with details of any equipment failures, is captured in the CMMS for historical reporting purposes.

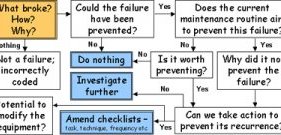

A logical response to this shop floor feedback is that the content of the checklists should be refined to improve the quality of the preventive maintenance, especially to prevent the recurrence of failures.

A common mistake however, is to jump straight from the work order feedback and immediately change the words on the checklists. When this happens, the integrity of the preventive maintenance programme is immediately compromised because the revised words on the checklist have no defendable scientific basis. This should be avoided wherever possible.

The far better approach to avoid this guessing game is to route all the checklist amendments through the same analysis as was used originally to create the initial checklists. This means that the integrity of the maintenance program is sustained over the long term. Implicit in this approach, however, is the need to have a robust system in which the content of the analysis can be captured and updated easily.

Finally, all the information that gets captured into the CMMS must be put to good use otherwise it is a waste of time. This is the value of management reports that can be created from maintenance information.

In the RCM analysis

In the RCM analysis

Without describing the complete RCM analytical process, it is instructive at this stage to point out a few details that are important to the content of such an analysis because of the way they can impact the overall maintenance plan.

Table 1 – Information captured in the RCM-style analysis

|

RCM |

Additional |

|

|

Identify the: |

Functions Functional failures Failure modes Failure effects |

Equipment hierarchy down to component level Root cause of failure |

|

Analytical tool to select: |

Failure effect category Preventive/ corrective maintenance tasks (as appropriate) |

|

|

Task frequency Crafts |

Task duration Running/stopped marker |

The center column is what will be found in any typical RCM-style analysis.

In addition to that, there is value in constructing a hierarchy of the equipment system showing assemblies, subassemblies and individual components. This helps to keep track of which section of the system is being considered at any time, and the list of components also helps to identify the spare parts requirements for the system.

Of vital importance is the clear identification of the root cause of each failure, as this will affect the selection of a suitable maintenance task. To illustrate this point, consider for example, a seized gearbox. “Seized” is an effect. There could be several root causes of this failure mode that can be addressed in different ways through the maintenance program. There is usually no value in aiming maintenance at the effect of a failure.

Also important from a planning perspective is to identify the time it will take to carry out each task independently. The sum total of these task times gives a good indication of how long the total work order will take.

All of the above depends on the production process and the site’s operating context, so these comments should be taken simply as a guideline.

The following are a few points to consider when constructing a preventive maintenance program:

Preventive maintenance tasks must:

- aim at the failure process

- be specific

- include specifications or tolerances

Wherever possible, aim for predictive rather than preventive tasks

- measure or check for conditions against a standard

- report the results

- create a follow-on task to repair or replace at the next opportunity

“Check and replace, if necessary” tasks destroy planned times

Frequencies and estimated times for each task must be accurate and meaningful

Try wherever possible to only plan shutdown time for “non-running” tasks. Keep “running” tasks to be done during periods of normal production. Structure the maintenance program to allow for this.

RELATED VIDEO

Share this Post

Related posts

Preventative Maintenance Systems

A is at the core of any efficient and well run facility. It is no secret that the ability to manage maintenance on a schedule…

Read MoreFleet Preventative Maintenance

Perhaps you already have a good grip on the little details of successful fleet management, like buying fuel-efficient vehicles…

Read More